They're like ATMs but they don't deliver money. There are more than 600 distributed in the suburbs of Nairobi, the capital of Kenya. The technology-based company KOKO strategically placed them in stores and markets and called them KOKO Points. Customers can buy bioethanol fuel in small quantities there for eco-friendly and economical cooking.

The inhabitants of the areas furthest from the urban center of Nairobi usually use gas, kerosene and charcoal to cook, but since the consolidation of the KOKO company project, bioethanol -cheaper, safer and less polluting- began to gain land among the inhabitants of this cosmopolitan metropolis.

Nairobi is the most populous city in East Africa, home to more than 4 million people. Its name means "the place of fresh waters", although it is known as the "green city in the sun".

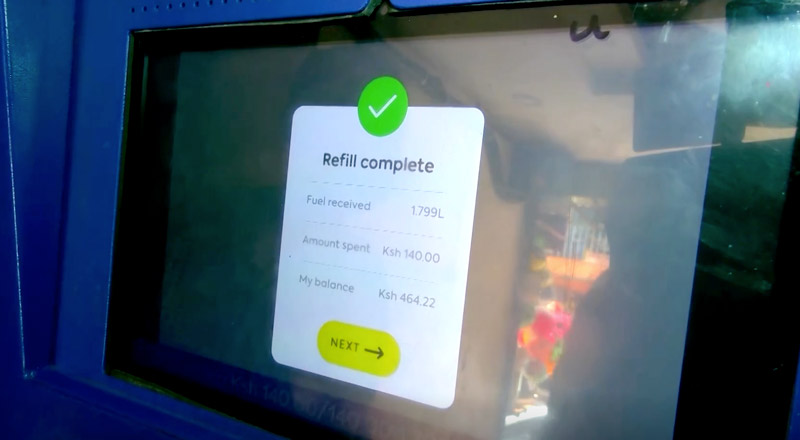

In addition to bioethanol, KOKO sells the stoves for US$40. The user receives it along with a reusable bottle that is identified with their mobile phone number and can make their fuel purchases through a digital account.

Those who turned to the use of ethanol for cooking in their homes or in food stores point out that their environments are no longer invaded by the black smoke emanating from coal. That black smoke was always a characteristic of the poorest communities.

“So far it's been very economical, no smoke, quicker to use when you're cooking. And it's easy to control," Regina Anyango, who runs a food business in Kangemi, a Nairobi neighborhood visited by Pope Francis in 2015, told VOA News and where she condemned what she called " the appalling injustice of urban marginalization”.

Kenya's capital is a place of contrasts between its high-rise urban center – with a strong British presence, a legacy of colonial rule that lasted until 1963 – and the suburbs where clean water is a scarce commodity. The country's food depends on small farmers who often have problems accessing financial resources and markets. Also, Nairobi is home to companies and organizations, including the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). In this context, the start-up KOKO emerged with its innovative project that combines technology and biofuel.

Michael Wakoli, head of Fuel Operations at KOKO, assured in VOA News that ethanol is a more practical and convenient fuel to use, and pointed out that self-service stations are in areas of Nairobi with large populations that are generally underserved. On the company's website they announced that the project will soon be extended to ten more cities in Kenya.

KOKO has had sustainable growth: since its launch in 2020 it has added more than 200 thousand clients and 500 employees.

Lower cost and fewer emissions

The United Nations Environment Program claims that bioethanol from sugarcane can reduce emissions by 40-62% compared to fuels derived from petroleum. Biofuels are substances produced with biomass or organic matter. Unlike fuels such as oil, coal or natural gas that come from energy stored for long periods in fossil remains, they are obtained from a renewable energy source and their production is much faster.

Bioethanol is an alcohol that is produced from different plant sources: starches are converted into sugars, these sugars are fermented and converted into ethanol, which is then distilled into its final form.

Sugar cane is the one that offers the most energy advantages, although corn is also used. Wakoli described the bioethanol produced in Nairobi as being based on molasses, a waste by-product of the sugar refining process.

More than 70 countries are working together to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and have pledged to enhance their international climate commitments under the Paris Agreement. How these promises from states and the private sector are translated into action will be crucial to ensuring that global warming can be limited to below two degrees Celsius. From the World Bank they maintain that countries still have the opportunity to chart a green and inclusive development path: “The decisions that are made now will determine the extent to which the world experiences new advances in development, the creation of sustainable jobs and an economic transformation. resilient and with low carbon emissions”, it says in one of its documents.

“Making the right investments can lead to short-term benefits—jobs and economic development—as well as long-term benefits for people, including decarbonization and resilience. Programs to incentivize low carbon emissions can drive the creation of new sustainable, inclusive and equitable jobs, ”he adds.

Africa represents only 2% of trade in the global carbon market, with South Africa and Nigeria leading the way. However, the African Development Bank (AfDB) launched a two-year technical assistance plan, the African Carbon Support Program. KOKO is part of this context, which although it is still an emerging development, is beginning to provide solutions in vulnerable contexts.

The company was created in 2014 and for the development and distribution of bioethanol it partnered with Vivo Energy, which distributes Shell and Engen fuels in Africa. Murray argues that companies like Shell are a kind of "artery" for the distribution of liquid fuel. KOKO's technology enables ethanol to reduce distribution costs. Customers pay in advance before picking it up at stores. They need, on average, at least a weekly bottle refill. Contact is frequent and regular.

Less smoke in homes

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 3 billion people around the world cook and heat their homes with open fires and stoves that burn biomass—wood, animal droppings, or agricultural waste—and Coal. Every year more than 4 million people die prematurely from diseases attributable to household air pollution as a result of the use of solid fuels for cooking.

In Kenya, more than 21,000 people die each year from diseases attributable to indoor air pollution. Therefore, KOKO's solution is based on a liquid fuel that burns cleaner and stores more safely. The network of local stores established by the company lowers costs and allows customers to buy in small quantities. By providing them with a reusable bottle, it prevents other plastics from being used.

Dirty fuels dominate the cooking market in Africa's 40 largest cities, says Greg Murray, CEO of KOKO Networks. Only high-income people can afford to use gas for cooking, those at the base of the urban pyramid do so with kerosene and charcoal, which are at the root of respiratory diseases, carbon emissions and deforestation.

***

This note is part of the platform Solutions for Latin America, an alliance between INFOBAE and RED/ACCION, and was originally published on Oct 11, 2021.

You can read this content thanks to hundreds of readers who support our human journalism with their monthly support ✊. Bank an open, participatory and constructive journalism: join as a co-responsible member.